Applying Dunning Kruger to Interviewing

Have you ever hired someone who you later realized over-sold themselves in the interview? What about someone who once on the job demonstrated they had under-sold themselves in the interview? There’s a world of difference between these two realizations and what they mean for you and your team’s productivity and satisfaction. By applying the Dunning-Kruger effect to interviewing, we can more reliably end up with people who perform even better than they indicated.

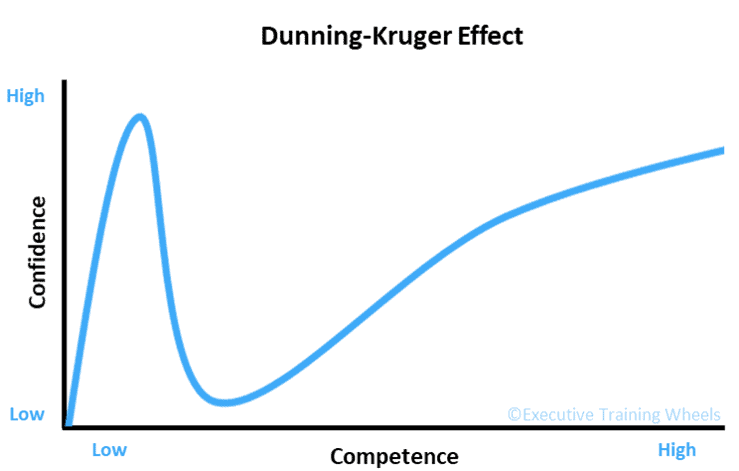

First, let’s do a quick introduction or refresher of the Dunning-Kruger effect, which shows why a little knowledge is a dangerous thing:

In the standard Dunning-Kruger framework, when we know nothing at all about a topic, we likewise have no confidence in it and are unlikely to opine on it. However, when we learn just a small amount, we quickly become overconfident. We haven’t yet learned how much there is to learn on this topic, so having learned something, we believe we’ve learned everything worth knowing. At this stage, our confidence and actual knowledge are so out of sync that we’re actually incapable of recognizing we’re incompetent. This is what many graphical representations refer to as “Mount Stupid,” the population of which consists of teenagers and all of us who forget to actively consider we may be wrong.

As we continue to learn and to gain exposure to that topic, we start to realize that there’s more we don’t know. A lot more. We learn that some of the first principles and basic rules we first mastered were just crude proxies. We see people who’ve mastered the subject, and we start to think we could never get to that point. Our dreams of world-domination on this topic dashed, we tumble down Mount Stupid into the “Pit of Despair.”

If we persist on after this blow to our ego, we learn more about the subject and start to become competent. We gain confidence with each new step, and we start to realize that we actually can get proficient at this. Unlike the exhilarating jetpack-fueled ascent of Mount Stupid, the journey up the “Slope of Enlightenment” is slow, steady, and challenging.

Eventually, as we proceed to mastery, we become comfortable with the fact that the topic is complicated. We hit the last inflection point where though we can continue to grow in our abilities, the increases in our confidence slow or stop altogether. We make peace with the idea that we will never know everything there is to know on it and that there will always be someone better at all or most of it. And because we realize these things, we never let our confidence get as high as it was when we crested Mount Stupid.

That’s interesting, but what does it have to do with interviewing?

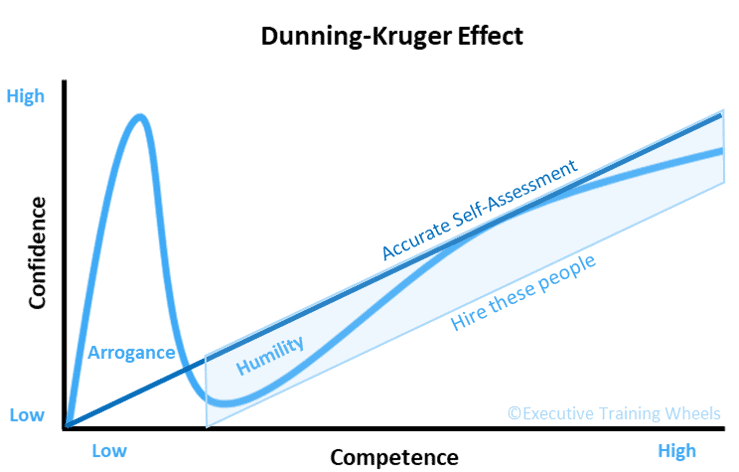

For one thing, the Dunning-Kruger effect illustrates a major reason why interviewing candidates effectively is so hard. Let’s look at it again, with one additional line:

Notice how rare it is for someone to have an accurate self-assessment of their abilities (where the two lines meet). Yet, to be an effective interviewer, you of course need to accurately assess their abilities.

“As an interviewer, you need to be a better judge of candidates’ abilities than they are of their own.”

Doug Bennett

When you interview someone, you need to determine their competence on the relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities for the role in question. In the graph above, you need to find out where they are on the x-axis. Most interviewers ask a lot of questions that effectively rely on a candidate’s interpretation of their own abilities, but we now understand that through no fault of their own, the candidate’s assessment is not to be believed!

When you’re hiring, you want to find someone who is both actually good at the role and humble enough to learn more. In light of the previous post, you want someone who shows they can admit when they are wrong. By applying the Dunning-Kruger framework to interviewing, you can tailor your approach to much more reliably identify such candidates.

To do so, we need to determine three things about a candidate:

- Where on the x axis they are (how competent they are)

- Where on the y axis they are (how confident they are)

- Where on the Dunning-Kruger curve they are

1. Where on the x axis they are (how competent they are)

For determining where on the competency axis a candidate is, there’s no better approach than a technical assessment (where possible). Depending on the topic, there are many existing ones out there, and there are firms that will make new ones for you. You can also make your own, just be sure to run it by someone qualified enough to confirm it’s not going to introduce bias.

In addition, penetrating questions help to expose actual competency. Picking a few claims or achievements on a candidate’s resume and asking them how they did it, why they did it that way, and then continuing to ask deeper “why” questions will show how deep or shallow that candidate’s knowledge is on the topic. It will also often expose whether the candidate had substantially more help than indicated. Having at least one of the interviewers be technically proficient in the area is recommended, as they will know how best to penetrate deeper on responses.

2. Where on the y axis they are (how confident they are)

For determining where on the confidence axis a candidate is, there are many questions we can ask. The most direct is simply to ask for a self-rating on a scale of 1-5 on the particular topic, and why. The earlier caveat that we can’t believe a candidate’s self-assessment doesn’t apply here. In this case, we already understand that their self-assessment is likely wrong; we just want to know what it says about their confidence level, not their competence.

On a related note, asking a candidate how they would define a 5/5 rating provides substantial insight into how much they think there is to know about a subject. For nearly any technical subject (software, tool, algorithm, etc.), a thoughtful answer on what a 5/5 would constitute should go well past simple proficiency and include multiple of the following:

- Teach it and create training material

- Discover new uses or applications for it

- Push boundaries with it, and know where they are

- Break it and fix it

- Know where and how to learn what you don’t know about it

- Know when to use it vs. something else

- Take any heavy or expert user and make them even better at it.

One more approach is to pick something they’ve done and ask if they’ve ever tried an alternative approach. This works best if you can offer a specific alternative that you are somewhat familiar with, and that they are unlikely to know well. Are they able to admit there are things they don’t know? Are they interested in learning about this alternative you proposed?

3. Where on the Dunning-Kruger curve they are

Once you’ve established a baseline estimate on their competency and confidence, you can start to determine where on the Dunning-Kruger curve a candidate is. Some candidates will actually tell you about their journey along the curve when they explain their self-rating, e.g. by explaining that they thought they were really good, then they were exposed to people who were much better, and now they give themselves a more modest rating. Such a response is incredibly useful, as it shows that they recognize they were on Mount Stupid, and that they are no longer there.

Behavioral questions (“tell me about a time when…”) have long been the gold standard in interviewing. One great thing about them, is they can be used to hone in on all three of the factors here, and which you get depends largely on your clarifying and follow-up questions. As you try to map out how competent this person is, how confident they are, and where on the Dunning-Kruger curve they are, tailor your follow-up questions to illuminate the parts you can’t well see yet.

Some behavioral questions very directly get to where on this curve a candidate is. Two examples I like to use are:

- Tell me about a time when you started to work on something, then realized it was substantially more complicated than you thought.

- Tell me about something you did previously where if you had to do it again, you’d take a different approach.

Each of these questions requires reflection on past times they’ve progressed down from Mount Stupid, and a good answer should reveal some progress up the Slope of Enlightenment. I’ve seen quite confident candidates get absolutely flummoxed by these questions, and some very humble and seemingly insecure candidates give enlightening answers.

Informed Hiring and Feedback

By actively assessing both how competent and how confident a candidate is, and understanding where on the Dunning-Kruger curve they are, we can tell before extending an offer which candidates will turn out to be even better than they indicated. While this may ruin the surprise of finding out a new hire is better than you thought, it also eliminates the negative surprise of finding out a new hire over-sold themselves.

When you identify a candidate who is in the humility zone and under-selling themselves, give them the same offer you’d give them if they had accurately assessed their strengths. Don’t lower the offer because you think their inaccurately low self-assessment means they’ll take it. Instead, build their confidence by giving them accurate feedback. This immediately engenders trust by showing them their leader is competent, fair, and genuinely cares for them.

This does not mean you should rule out those who already have an accurate self-assessment! Such people are rare to find, and the above framework will help you to recognize them when you interview them, rather than be blinded by their confidence and mistake their actual abilities for puffery. We want our teams to know what they are capable of. We want them to have the confidence to try new things and take educated risks. Accurate self-assessors give your team a head start.

The shape of the Dunning-Kruger curve is not fixed, and it is not the same for everyone. The more you can influence the shape of the curve for the members of your team to reflect accurate self-assessment, the more your entire team will believe in themselves, each other, and you. This goes a long way toward building a team of people who are good at identifying and evaluating talent, which is the first step toward developing people at scale.

3 Comments

Leave your reply.