Turn Impostor Syndrome to your Advantage

The past two posts have talked about the importance of humility for effective leadership, which will be a recurring theme. At this point it’s worth noting that there are negative side effects of too much humility. One of these negative effects is the impostor syndrome, and it is especially common in Analytics. As a leader, it’s important to be able to identify when you have impostor syndrome and know how to overcome it. You also need to be able to identify it in others and help them overcome it. Ultimately, you can turn impostor syndrome around and use it to your advantage in building a team with tremendous capacity and flexibility.

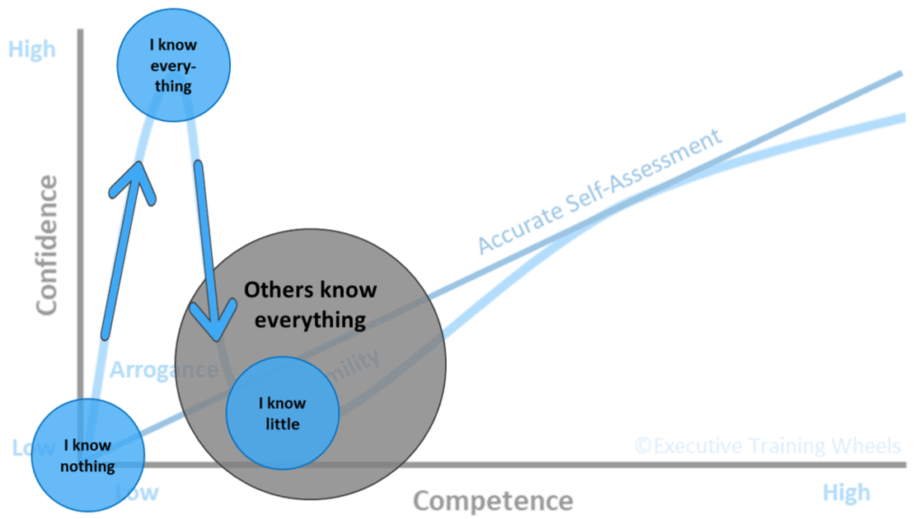

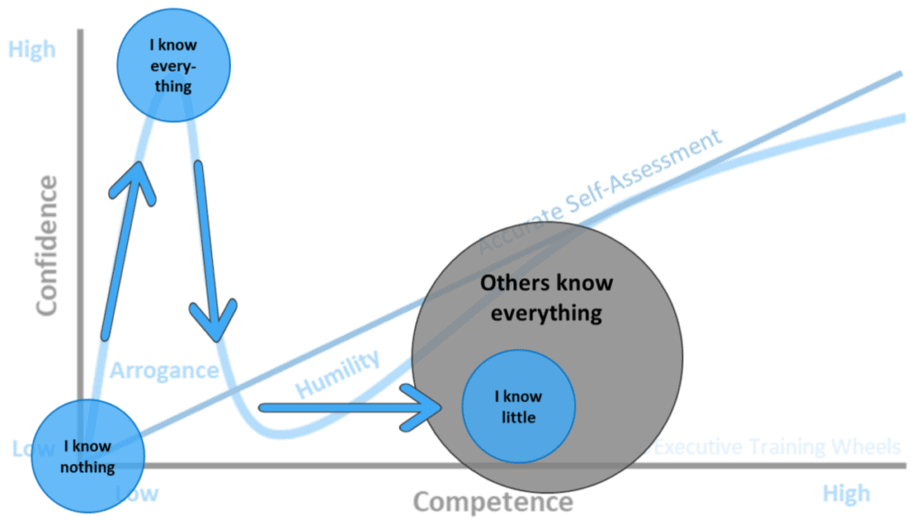

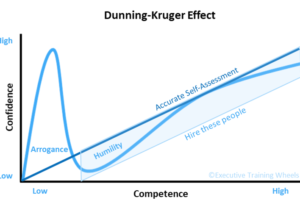

In the previous post we showed how to use the Dunning-Kruger effect to your advantage in interviewing. Early in the post, we noted that the inflated confidence that comes from a little bit of knowledge quickly starts to erode when we see people who’ve mastered that subject. We realize we know far less than we thought, and we start to think we could never get to the point of mastery. In the Dunning-Kruger graph, it’s represented as a rapid descent into the “Pit of Despair”, where our confidence ends up significantly below our actual ability.

It’s common to get stuck in this state of self-doubt, especially when you are continually exposed to people who know things you don’t. In fact, the more you’re exposed to competent, knowledgeable people, and the more humility and openness to learning you have, the more likely you are to stay in this low-confidence state even when your actual abilities are still increasing.

This can pull you below the Dunning-Kruger curve and past the point of humility into insecurity. This phenomenon is known as impostor syndrome, because of the way it makes perfectly competent and knowledgeable people believe they are impostors who don’t actually know much.

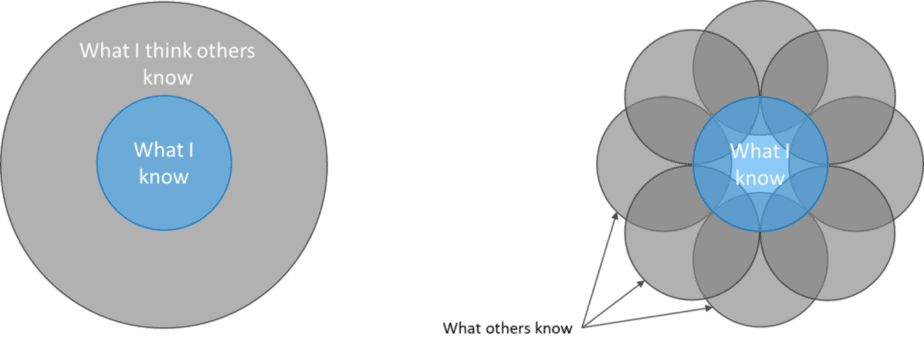

The antidote for impostor syndrome is to take a closer look and realize what’s really happening:

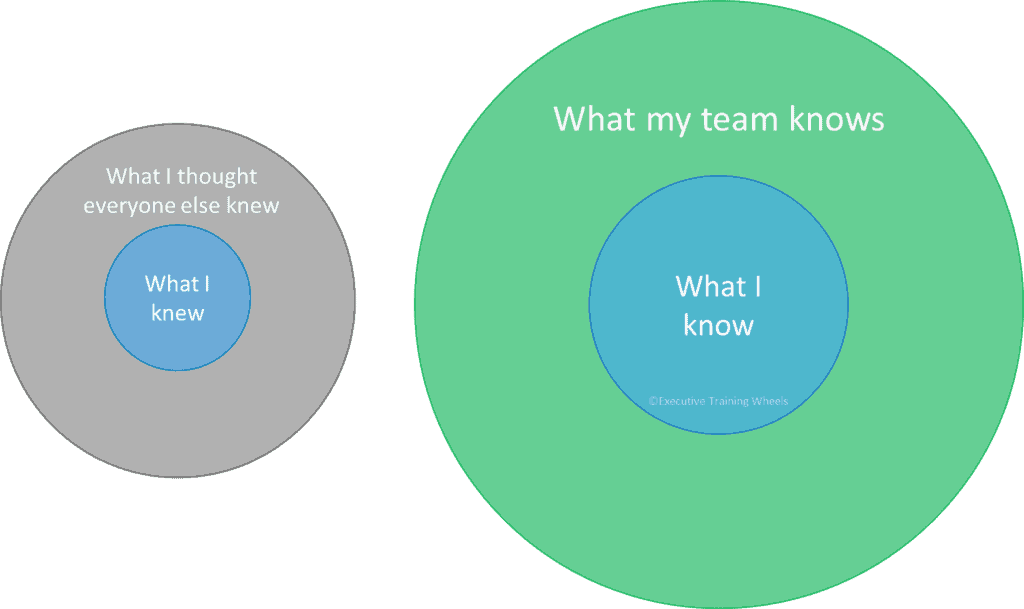

When you look more closely and force your lazy brain into remembering that the “others” you’ve been comparing yourself to are individuals and not a hive-mind, your self-assessment becomes much more nuanced and much less depressing.

That others know so much you don’t is still humbling, but now in a very different way. It’s amazing just how much so many people know, and they all know different pieces or combinations. You may actually know as much as many of them, just your knowledge is in slightly different areas than theirs, and vice versa. What a relief!

The fact that there’s still a lot out there that you don’t know hasn’t changed. What has changed is your understanding of how fractured that knowledge is, with it spread across so many people, each holding and nurturing their own fragment.

What if we could bridge more of the gaps between people who know different things from each other, but who each have some overlap with what we know? The result would be a team vastly more capable than any individual member, and which has the potential to create knew knowledge and capabilities not yet possessed by anyone. You can turn impostor syndrome around and use it to your advantage as inspiration for building such a team.

The realization of what impostor syndrome is and why you perceive it can be enough to pull you out of the Dunning-Kruger Pit of Despair. As you build your team up and make more connections, you build each other’s confidence as you all learn.

By definition, if you’ve experienced impostor syndrome, you’ve already progressed past Mount Stupid in the Dunning-Kruger framework (at least for that topic). And because what’s fueling your greater confidence now is the very fact that you know there’s a ton you don’t know, and that to address that you’ve assembled a team of people who do know, you’re unlikely to use your boosted confidence to climb back up Mount Stupid.

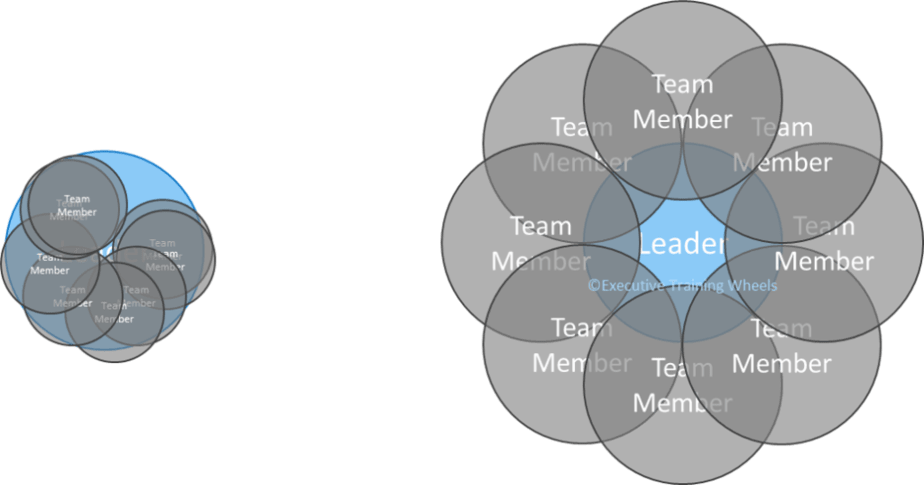

When you’re able and willing to hire those who know things you don’t, you can stitch together a tapestry of talent that covers far more area than your own abilities. Let’s look at what happens when you take the impostor syndrome epiphany and use it to your advantage in building a team.

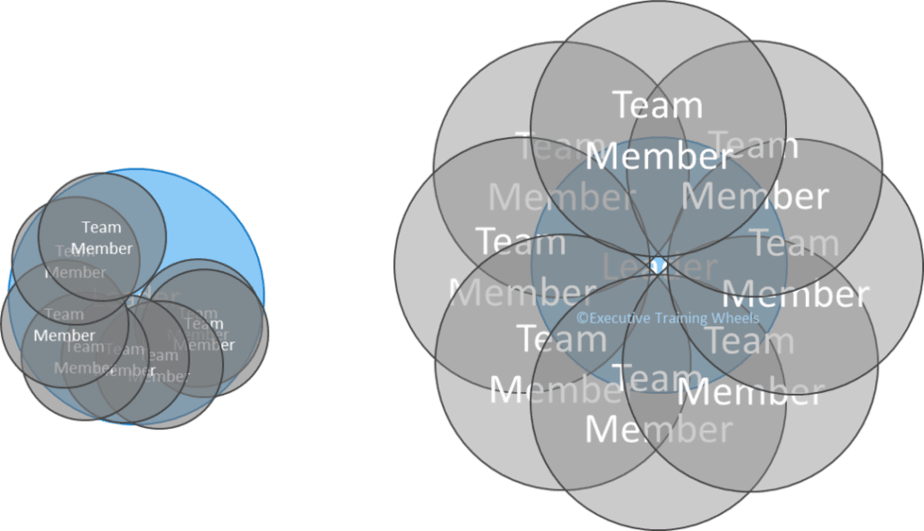

Above are two teams, with equally capable leaders. The first leader is insecure and has sought to build a team of people who don’t threaten them. They’ve hired people who are less knowledgeable than they are, and whose knowledge does not extend too far past the leader in any area. The second leader has experienced impostor syndrome, gotten past it, and turned it around to their advantage. They’ve done their best to hire people at least as smart as they are, and who know things they don’t.

This calls to mind a quote from an entrepreneurship professor of mine in college:

A level people hire A level people. B level people hire C level people.

The way these leaders have chosen to build their teams has profound impact on how they will be spending their time. The first leader has direct involvement and say in nearly everything their team does. In most cases, anything being done by a team member could be done better and faster by the leader. As a result, the leader will end up micro-managing whether they want to or not. The necessity that this leader be personally involved in nearly every task will contribute to burnout and prevent them from having time to spend learning or strategizing. By contrast, the second leader is able to assign any given project to the right people on their team and know that it will be done well.

Let’s fast-forward a year or so. The second leader, who intentionally built a team of people who have a lot to teach each other, has grown their own and their team members’ knowledge radius by a third. To be generous, let’s say that the first leader has also somehow grown themselves and everyone on their team at the same rate, despite neither being structured for it nor having the time for it:

Because everyone in both teams has grown, there’s now substantially more overlap than there was before. In the first team, this additional overlap can mitigate the leader’s need to constantly micromanage. However, due to this leader’s insecurity, they have carved out an area of knowledge on the team to hold in reserve for themselves. They won’t teach team members anything in this particular area, as they believe being the only one capable of doing it gives them job security and protects their position of importance. I call this the bandage theory of job security. They’re counting on whoever is above them to prefer suffering for an extended time over bearing the short-term pain of ripping the bandage off and removing the leader that’s stifling their organization.

In the second team, each team member now has significant overlap with four other team members plus the leader. This further accelerates the potential for knowledge sharing and new knowledge creation. It also starts to provide more protection from the cost of attrition, as even though each team member has capabilities no one else has, the gap between them and the two closest team members has shrunk. Additionally, since the leader is now able to effectively delegate nearly anything that needs to be done, they have the slack to make an immediate shift in the direction of the gap until a real solution is found. In doing so, they will gain even more new knowledge and abilities.

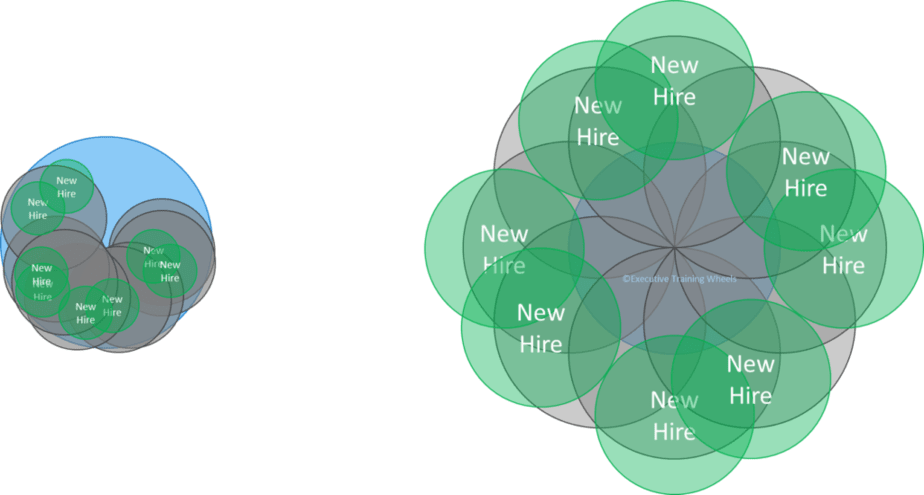

Let’s fast-forward another year. This time, we’ll assume that four of the 8 team members each leader previously had have now been able to hire two more team members each. We’ll again assume a one third increase in knowledge radius for everyone on both teams, which is generous to the first team:

The “New Hire” circles are substantially different between these two teams. This is because of the effect each leader had when they first built their team, and in how they have chosen to manage learning and development in the time since. The team members under the first leader have emulated that leader by hiring people who are less knowledgeable than they themselves are, and they have also been careful not to hire people whose knowledge extends enough beyond their own to ever pose a threat. As a result, despite doubling the number of employees this leader has, they’ve gained no new capabilities at all. They have more bandwidth for doing things they were already doing, and that’s it.

In the second team, the team members have likewise emulated their leader. They’ve hired people who, although they don’t know as much as the hiring members, know as much as the hiring members did two years ago when they themselves were hired. They’ve also selected new hires who bring additional capability to their team. This team has again expanded its total capabilities, and each new hire has overlap with another new hire, three veteran team members, and the original leader.

By this stage there has been a subtle change on the second team that the leader will likely struggle with, and it is an issue the first leader will never encounter. Look again at the second team in the visual above, this time specifically at the leader. There is no longer any area this team covers where the leader has the most in-depth knowledge or capability. In late 2017 I came to the realization that the team I’d built had hit this point, and it was deeply unsettling. It’s one thing to be impressed by the amount of expertise on your team across a variety of topics. It’s another to realize that on any one of those topics the recognized expert is not you.

This realization can cause a tailspin into a version of impostor syndrome that is much harder to escape. This time, the fact that it’s multiple other people who each know different things is something you already understand- you intentionally going after that is what got you into this situation! Worse, there are not nearly as many people who have had this realization and come out the other side of it as there are people who’ve been through the traditional version of impostor syndrome. You can’t count on someone recognizing what’s troubling you and showing you the solution.

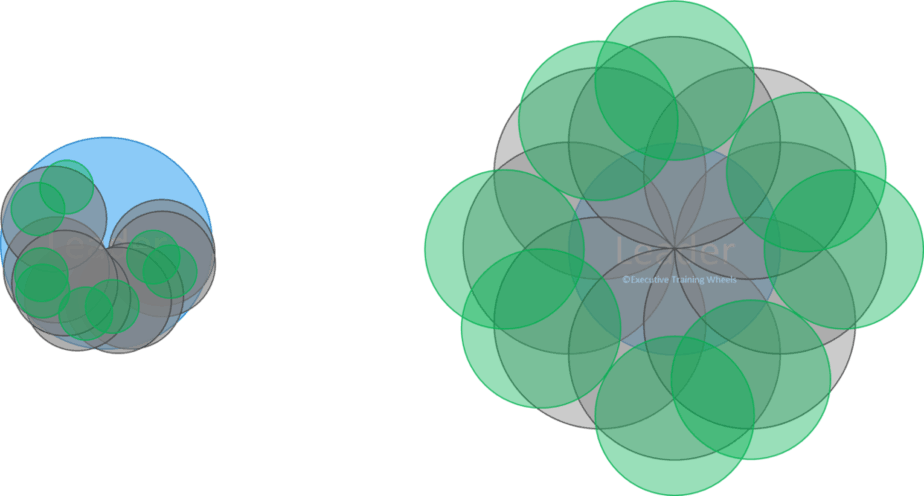

One potential response would be to seek to outgrow the problem by brute force. You could try to learn something that no one on your team knows. But look again at that team. The capability is so vast, you’d have to go far outside your area of expertise to get into something no one else knows already, you’d have to beat them to it, and you’d have to do it without their help. How much of your valuable bandwidth would that tactic cost?

Another approach would be denial. All you have to do then is just make sure no one else notices that you’re not actually the foremost expert on anything anymore. Bullshitting your way through meetings and taking credit for the work your team members do is certainly an easy way to avoid wrestling with this issue. For a little while, it can even seem effective.

Alternatively, you could eliminate the problem by eliminating or reallocating a few people on the team and shifting to a structure more like the first leader’s team. You’ll lose team knowledge and capacity and might torch some relationships with team members you hired and mentored, but that’s a small price to pay for protecting your ego. Right?

The first of the three options above is borderline suicidal, and the latter two are reprehensible. People who’ve led careers to a point where they’ve built teams like this are likely to have at least a portion of their identity wrapped up in the fact that they’re the foremost expert in some part of their area. The only reason I bring up those three tactics is because many people will do nearly anything to avoid having to grapple with a threat to their self-identity. It’s important to understand the damage that a blind and selfish decision in the face of this next-level impostor syndrome could have.

Fortunately, there is a solution to this more advanced version of impostor syndrome, and it is again a matter of perspective. The first step is realizing that you’re still playing a vital role.

Good people working hard with good intentions isn’t enough. You need vision. You need leadership. Someone needs to coordinate their efforts toward the right end.

General Stanley McChrystal, Team of Teams

The simple fact is that there already is something on which you are the foremost expert- how to run your high-performing team. You have more overlap with the members of your team than anyone else does. You can coordinate team learning, individual development, and set the team strategy and vision in ways no one else can. You established the team’s pattern of accountability and remain responsible for maintaining it, ensuring each of these incredibly capable people are working on the right problems at the right time. There are multiple other things leaders in this situation can do to add massive value. Many of them will show up as topics of future posts.

As you go through this journey in building a team, a network, or any other group of talented individuals, keep the big picture and end goal in mind. And when you get to the point in the image below, remember to take a step back and congratulate yourself before you press further or start over again with another team.

3 Comments

Leave your reply.